Paging through Victorian era magazines you will find thousands of dull, unimaginative illustrations that long ago ceased to have relevance to anyone. But every once in a while you find an illustration that leaps off the page, grabs you by the lapels and shakes you. The rare artist with "the spark" still stands out.

Paging through Victorian era magazines you will find thousands of dull, unimaginative illustrations that long ago ceased to have relevance to anyone. But every once in a while you find an illustration that leaps off the page, grabs you by the lapels and shakes you. The rare artist with "the spark" still stands out.

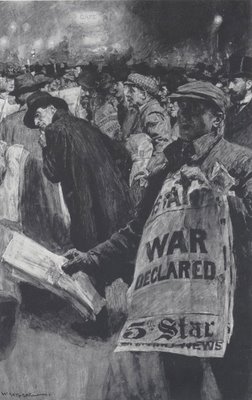

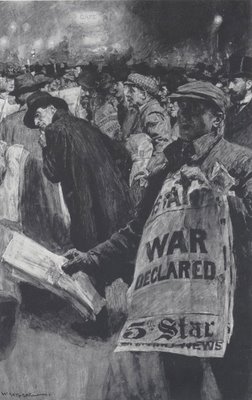

Most of his peers have been blissfully forgotten, but English illustrator William Hatherell (1855-1928) had "the spark" and deserves to be remembered for it.

This drawing overcomes every disadvantage that the world could throw in its way: working in black and white with charcoal and wash, reproduced in a publication with poor printing quality in a period when the prevailing style was largely fusty and stolid, Hatherell produced a picture of striking strength and vitality measured by the most modern standards.

His composition has all the verve and excitement of an illustration from America in the 1960s. His potent use of values, his vigorous strokes and the careful placement of figures result in a picture more dynamic and lively than much of what is produced today using the latest computer graphic technology. It just goes to show you that even if you are born in the wrong place and time, working with the wrong tools, sheer talent can do a lot to level the playing field.

I don't have access to the original of this drawing by Hatherell, but I am attaching below some details from another one of his drawings so you can see his technique.

Hatherell worked on the staff of a magazine called The Graphic starting in the early 1890s.

Hatherell worked on the staff of a magazine called The Graphic starting in the early 1890s.

In less capable hands, this drawing would lapse into a nondescript puddle of gray. Only Hatherell's mastery of value maintains the integrity of the picture.

In less capable hands, this drawing would lapse into a nondescript puddle of gray. Only Hatherell's mastery of value maintains the integrity of the picture.

You won't find much of his work around these days, but this was a man who could draw.

You won't find much of his work around these days, but this was a man who could draw.

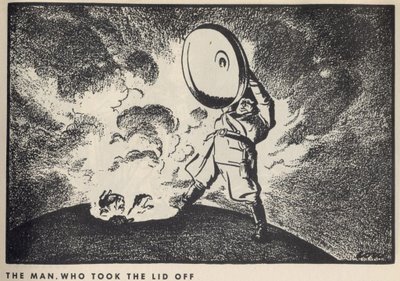

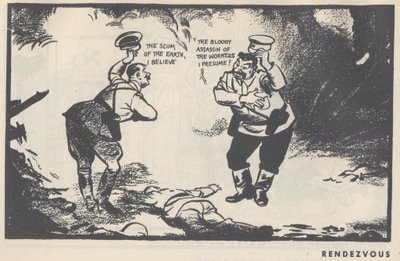

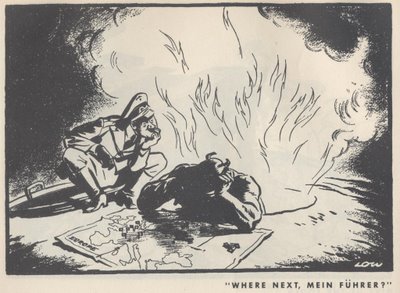

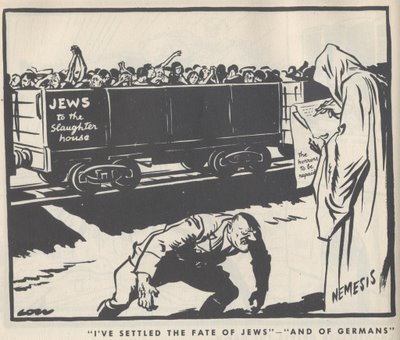

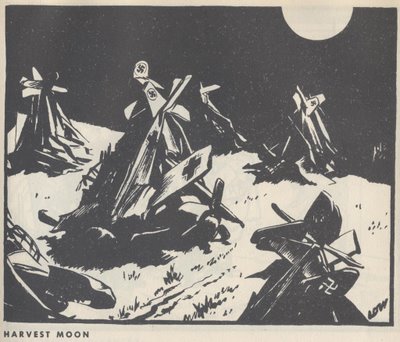

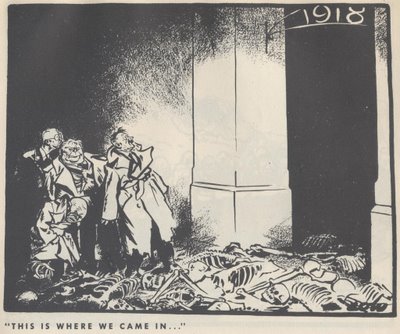

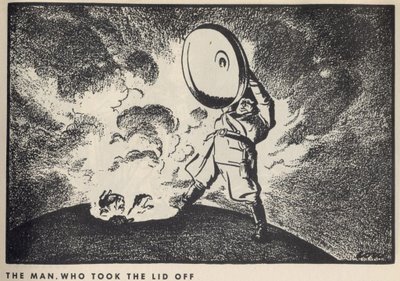

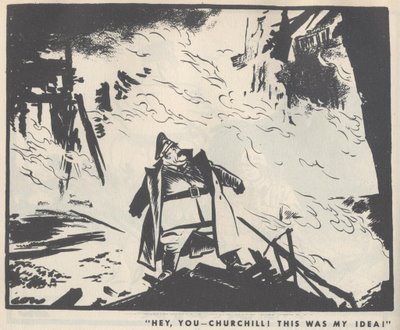

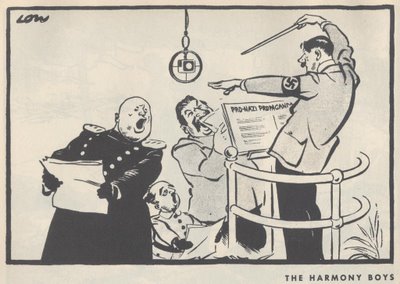

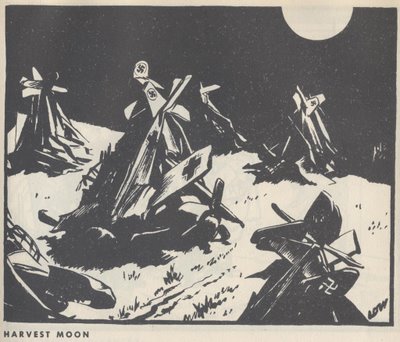

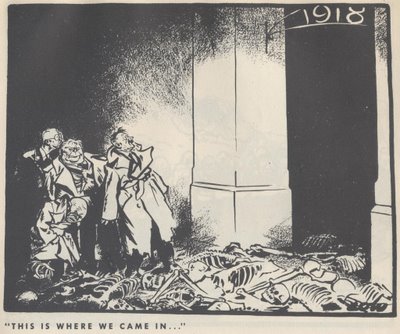

Perhaps the best political cartoonist to emerge from the smoking cauldron of World War II was David Low. The power of his simple, clear drawings took him halfway around the world and protected him from many forms of censorship.

Perhaps the best political cartoonist to emerge from the smoking cauldron of World War II was David Low. The power of his simple, clear drawings took him halfway around the world and protected him from many forms of censorship.

Low was born in a small town in New Zealand in 1891. He learned to draw from studying the pictures in old magazines in the back of a second hand bookshop. The popular style when Low was growing up was fancy, elaborate linework the way Charles Dana Gibson, Charles Keene and Norman Lindsay drew. Low wanted a simpler, cleaner look. His goal was to combine "quality with apparent facility."

Low was born in a small town in New Zealand in 1891. He learned to draw from studying the pictures in old magazines in the back of a second hand bookshop. The popular style when Low was growing up was fancy, elaborate linework the way Charles Dana Gibson, Charles Keene and Norman Lindsay drew. Low wanted a simpler, cleaner look. His goal was to combine "quality with apparent facility."

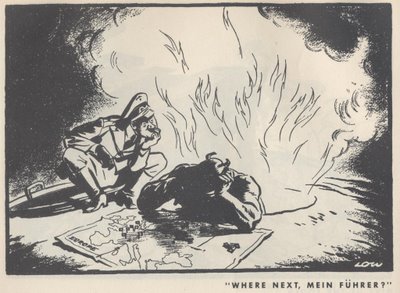

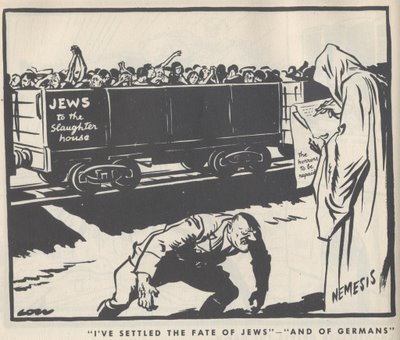

Low's direct, powerful style stood out from other editorial art of the day and brought him to the attention of local New Zealand publications, which then brought him offers of employment from Australia, and later from England where the richest and most powerful newspapers bid fiercely for his services. From this forum, Low waged a brilliant graphic assault on the Nazis.

Low's direct, powerful style stood out from other editorial art of the day and brought him to the attention of local New Zealand publications, which then brought him offers of employment from Australia, and later from England where the richest and most powerful newspapers bid fiercely for his services. From this forum, Low waged a brilliant graphic assault on the Nazis.

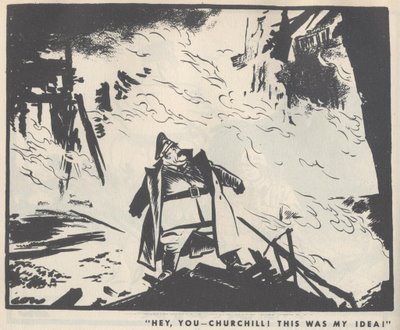

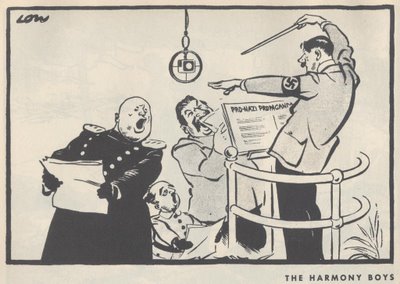

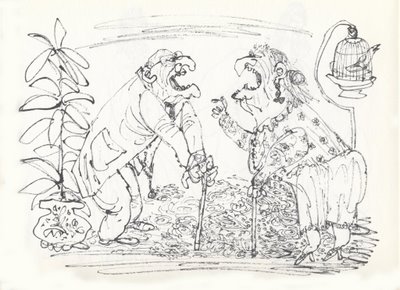

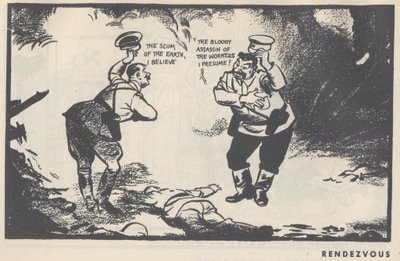

Low's art was not as simple as it looked. He later wrote, "making a cartoon occupied usually about three days: two spent in labour and one in removing the appearance of labour." You can see Low's hard work below the surface in the beautiful body language and facial expreessions of Stalin and Mussolini singing above, or in the salutations of Hitler and Stalin below. Note the tilt of the heads and the angles of the bodies. These are wonderfully choreographed drawings with simple, powerful darks and whites.

By studying the originals up close (see next image) you can see just how blunt and uncluttered Low's brushwork was. He worked large-- a typical cartoon would be 14 x 17.

By studying the originals up close (see next image) you can see just how blunt and uncluttered Low's brushwork was. He worked large-- a typical cartoon would be 14 x 17.

I love Low's no-frills drawing. Its honesty and toughness stood up to many a powerful enemy. Low was an ardent socialist but he was so good that the staunchly conservative Lord Beaverbrook begged Low to come work for Beaverbrook's newspaper, The Evening Standard. Beaverbrook promised to double Low's salary and give him complete artistic freedom. Beaverbook later grumbled that Low was trying to comandeer the whole paper's editorial policy, but he never dared to censor Low's voice.

I love Low's no-frills drawing. Its honesty and toughness stood up to many a powerful enemy. Low was an ardent socialist but he was so good that the staunchly conservative Lord Beaverbrook begged Low to come work for Beaverbrook's newspaper, The Evening Standard. Beaverbrook promised to double Low's salary and give him complete artistic freedom. Beaverbook later grumbled that Low was trying to comandeer the whole paper's editorial policy, but he never dared to censor Low's voice.

Hitler was enraged by Low's scathing drawings, and the Nazi government formally requested that the British government "bring influence to bear" to stop Low. However, nothing was done. After World War II, objections came from the opposite side of the fence: Winston Churchill claimed that a cartoon about the situation in Greece should be blocked "in the interests of western democracy."

Hitler was enraged by Low's scathing drawings, and the Nazi government formally requested that the British government "bring influence to bear" to stop Low. However, nothing was done. After World War II, objections came from the opposite side of the fence: Winston Churchill claimed that a cartoon about the situation in Greece should be blocked "in the interests of western democracy."

Once upon a time, the ability to draw with strong, clear lines and a sharp eye could take you from a small town in New Zealand to the center of the world stage in London where powerful publishers and world leaders would rail against you, to no avail. Low was ultimately protected by the beauty and directness of his work.

Once upon a time, the ability to draw with strong, clear lines and a sharp eye could take you from a small town in New Zealand to the center of the world stage in London where powerful publishers and world leaders would rail against you, to no avail. Low was ultimately protected by the beauty and directness of his work.

For most of the 20th century, the primary gripe against illustration was its simple-minded content. No matter how talented or skillful the artist, illustrations for silly romantic fiction in women's magazines or childish advertising slogans just could not be taken seriously.

For most of the 20th century, the primary gripe against illustration was its simple-minded content. No matter how talented or skillful the artist, illustrations for silly romantic fiction in women's magazines or childish advertising slogans just could not be taken seriously.

How odd, then, that in recent years this situation has completely reversed: we have changed from sophisticated illustrations of cartoonish subjects to cartoonish illustrations of sophisticated subjects. Illustrators now deal with the most adult and graphic content, but do so using simple, child-like forms.

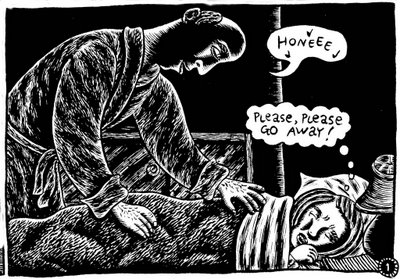

Art Spiegelman's crudely drawn comics of talking mice confronting torture and genocide in Nazi death camps won Spiegelman a pulitzer prize.

Art Spiegelman's crudely drawn comics of talking mice confronting torture and genocide in Nazi death camps won Spiegelman a pulitzer prize.

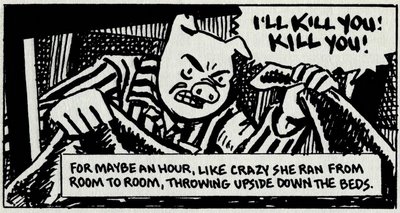

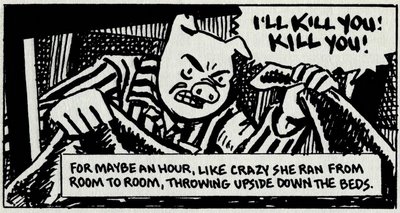

Child-like pictures by Debbie Drechsler convey blood curdling stories of incest and molestation

Child-like pictures by Debbie Drechsler convey blood curdling stories of incest and molestation.

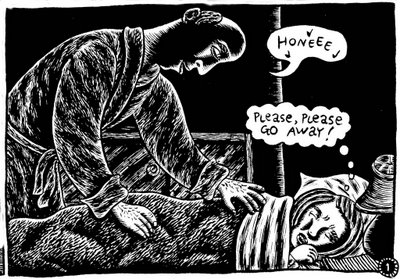

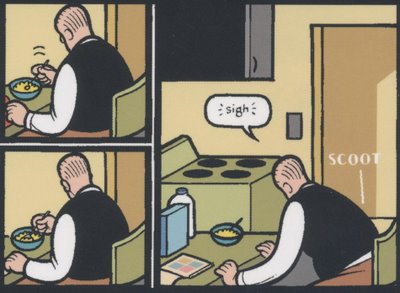

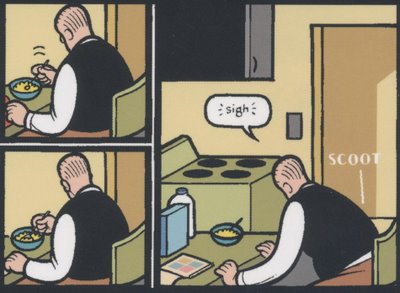

Chris Ware portrays bleakness and alienation using simplistic diagrams reminiscent of industrial instruction manuals.

Chris Ware portrays bleakness and alienation using simplistic diagrams reminiscent of industrial instruction manuals.

This trend is evident from the changing mix of artwork in the annuals of the Society of Illustrators. It can also be seen in the work of the "new illustrators" group, the "concept art" crowd and the innovators behind "Raw." What is happening here? Why have form and content switched places in modern illustration? And what does that say about the evolution of our society?

I suspect that there are multiple forces at work. Clearly, illustration lost much of its ambition for technical skill as it fled from the path of the camera. There was not much point in investing years of rigor and discipline to develop skills if illustrators (and the publications that sustained them) were destined to lose the battle to television and photography anyway.

It also seems pretty clear that many of today's innovators didn't want to compete on the home turf of the great illustrators who preceded them. Seymour Chwast confessed that he stays away from techniques and media “that require craftsmanship and a drawing ability I do not have.” Elwood Smith, another highly regarded "cartoon-style" illustrator, recounts that when he tried to draw like the twentieth century “old master” artists with pen and ink, he simply couldn’t do it. But, he says, his inability to render the picture in his mind leads to greater innovation: “if I can’t draw it, I struggle to come up with a different idea that’s invariably more original.” The same could be said of a number of other contemporary illustrators who have shifted the direction of modern illustration.But there are other, more legitimate reasons for the transformation to child-like styles. Recently, it seems that audiences and creators have become so saturated with mature content that they have become virtually shock proof. It is hard to envision a single vice that has not received ample, repeated and graphic airing. Perhaps for that reason, artists reach for simple, child-like images to reach audiences at a more susceptible and vulnerable level.

The great Mark Twain found that he could create a fresh perspective on adult corruption, greed and slavery by describing them through the eyes of an innocent young boy, Huckleberry Finn. Ever since then, artists have made creative use of the contrast between adult and child-like in various combinations. In the 1950s, Charles Schulz revolutionized the comic strip by putting adult wisdom in the mouths of simply drawn little children. Mel Lazarus used a similar approach with the beautifully drawn Miss Peach.

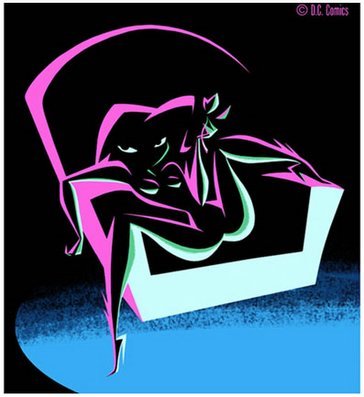

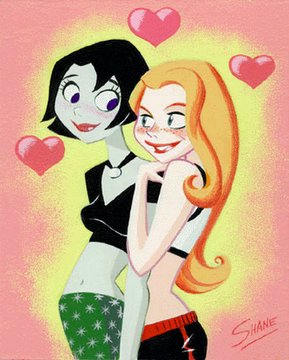

One interesting example of this trend is the use of a simple and innocent 1950s visual style from Disney animated movies and Golden Books to convey a more wicked subject matter. This juxtaposition of form and content can evoke surprising reactions. One of the very best at this is Shane Glines, a creative and prolific young artist with an excellent design sense.

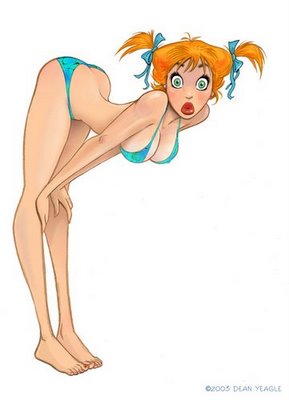

Another such artist is Dean Yeagle. These two, along with other illustrators, seem to be mixing spicy content with innocent images in creative ways. I enjoy their work.

Another such artist is Dean Yeagle. These two, along with other illustrators, seem to be mixing spicy content with innocent images in creative ways. I enjoy their work.

There is of course a larger issue that I have not addressed yet: why do illustrations with mature content but mediocre drawing merit museum shows, laudatory reviews in the New Yorker and pulitzer prizes, while illustrations with simplistic content and superb drawing are chronically snubbed? For example, comic strips like Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond (which had brilliant drawings of goofy stories) will never be accorded the respect that comic strips like Maus or Jimmy Corrigan (which have unimpressive drawings of serious stories) receive. As you might imagine, I have some thoughts on this too, but I have blathered on far too long for one day.

There is of course a larger issue that I have not addressed yet: why do illustrations with mature content but mediocre drawing merit museum shows, laudatory reviews in the New Yorker and pulitzer prizes, while illustrations with simplistic content and superb drawing are chronically snubbed? For example, comic strips like Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond (which had brilliant drawings of goofy stories) will never be accorded the respect that comic strips like Maus or Jimmy Corrigan (which have unimpressive drawings of serious stories) receive. As you might imagine, I have some thoughts on this too, but I have blathered on far too long for one day.

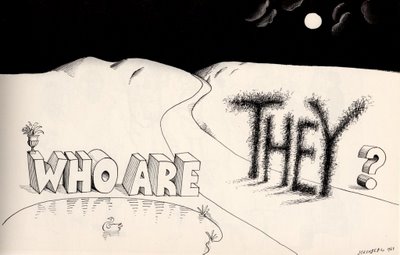

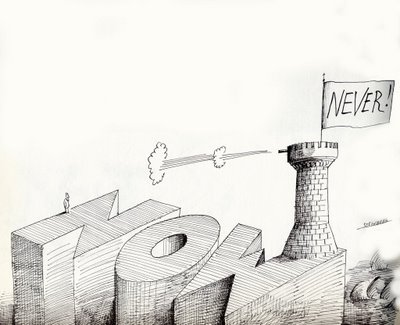

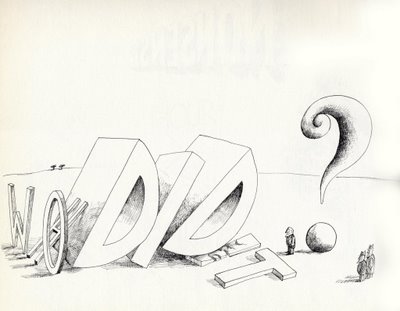

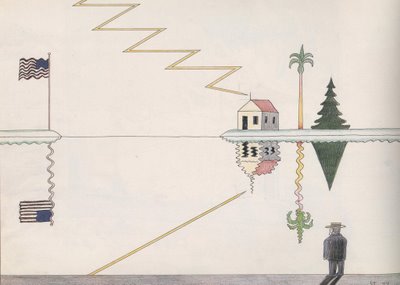

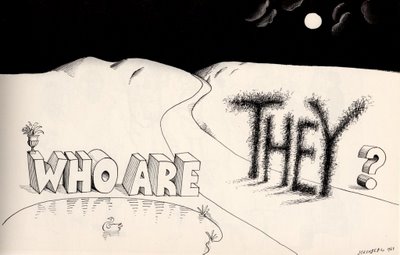

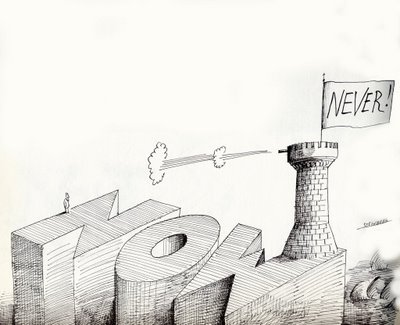

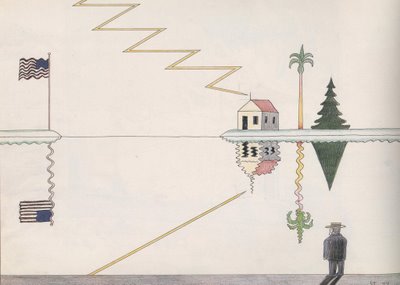

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In the whole long clanging pageant of art, no artist ever combined words and pictures the way that Saul Steinberg did. He was truly an original. When Steinberg died, art critic Robert Hughes wrote, "He had no equals. Now he has no successors." The critic and philosopher Harold Rosenberg noted with admiration,"there is only one of his kind."

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYSteinberg dealt with the most immense and challenging issues of the human condition. New York Times art critic John Canaday wrote, "Steinberg is the great artist of the post World War II quarter-century and maybe, for all we know now, the whole latter half-century." But for all his depth and brilliance, Steinberg had a playful side that showed itself in simple little word pictures like these.

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYSteinberg dealt with the most immense and challenging issues of the human condition. New York Times art critic John Canaday wrote, "Steinberg is the great artist of the post World War II quarter-century and maybe, for all we know now, the whole latter half-century." But for all his depth and brilliance, Steinberg had a playful side that showed itself in simple little word pictures like these.

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

These drawings reveal Steinberg's imagination at the granular level. He was quite capable of constructing elaborate, multi-tiered works of great profundity, but unlike today's image-conscious artists who work with press agents to shape their image and protect the mystery of their creativity, Steinberg was never afraid to put these little drawings on display. To borrow a phrase from Issac Stern, these drawings "make it so simple that you can't cheat."

I admire Steinberg as much for his backbone as for his clear artistic gifts. He was never afraid that his playful cartoons would dilute the brand of his museum paintings and sculpture.

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYI have used this blog to disparage "concept artists" who delude themselves that the high falutin' content of their message will redeem their otherwise meager artistic talents. Steinberg is one artist who got it right-- brilliant content married to a strong and excellent visual form.

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYI have used this blog to disparage "concept artists" who delude themselves that the high falutin' content of their message will redeem their otherwise meager artistic talents. Steinberg is one artist who got it right-- brilliant content married to a strong and excellent visual form.  © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYSaul Steinberg was one of the greatest illustrators of all time. He was so damn smart you could warm your hands by the intellectual glow from his drawings. Yet, his brilliant content never overpowered his images. Art critic Robert Hughes wrote that Steinberg exhibited a form of "graphic intelligence that had not been imagined in American illustration before him."

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYSaul Steinberg was one of the greatest illustrators of all time. He was so damn smart you could warm your hands by the intellectual glow from his drawings. Yet, his brilliant content never overpowered his images. Art critic Robert Hughes wrote that Steinberg exhibited a form of "graphic intelligence that had not been imagined in American illustration before him."

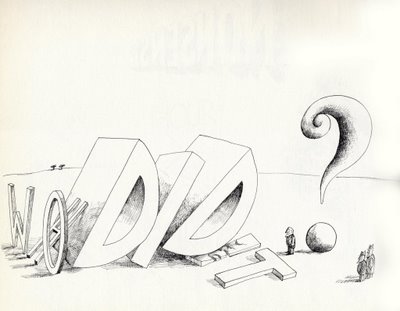

This lovely drawing is not one of his more famous or elaborate images, but I selected it because it shows very simply how Steinberg's mind provides fresh insight into the most elemental ingredients of our world: as he scans the horizon line, he plays with the fact that water makes straight things crooked, then uses that to make crooked things straight (the evergreen, the lightning bolt) and ends with the coup de grace: the straight flag pole is now corrugated but the waving flag has become straightened!

Steinberg's art could never be contained by words or images alone. He really required the marriage of the two. He was perhaps the 20th century's leading example of illustration as an irreducible art form.