Perhaps the best political cartoonist to emerge from the smoking cauldron of World War II was David Low. The power of his simple, clear drawings took him halfway around the world and protected him from many forms of censorship.

Low was born in a small town in New Zealand in 1891. He learned to draw from studying the pictures in old magazines in the back of a second hand bookshop. The popular style when Low was growing up was fancy, elaborate linework the way Charles Dana Gibson, Charles Keene and Norman Lindsay drew. Low wanted a simpler, cleaner look. His goal was to combine "quality with apparent facility."

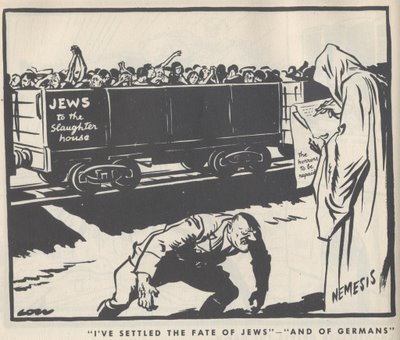

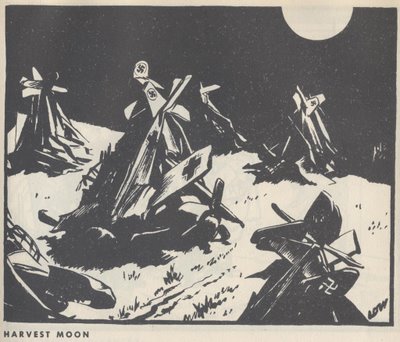

Low's direct, powerful style stood out from other editorial art of the day and brought him to the attention of local New Zealand publications, which then brought him offers of employment from Australia, and later from England where the richest and most powerful newspapers bid fiercely for his services. From this forum, Low waged a brilliant graphic assault on the Nazis.

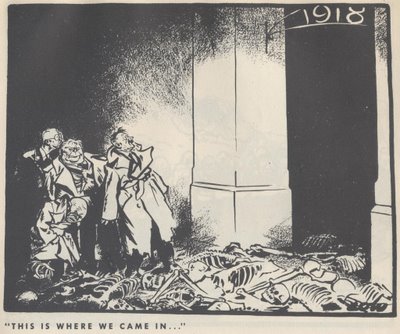

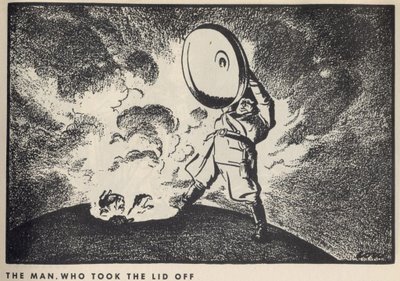

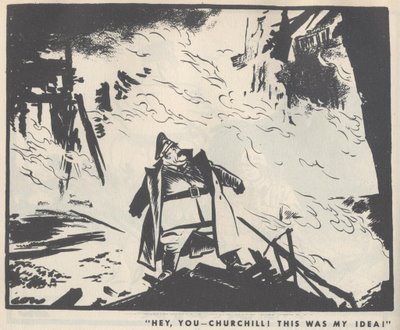

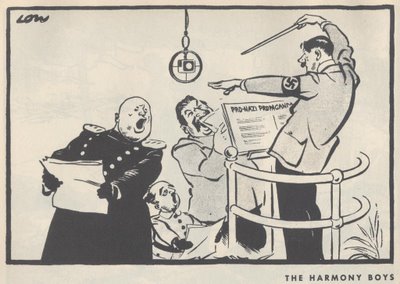

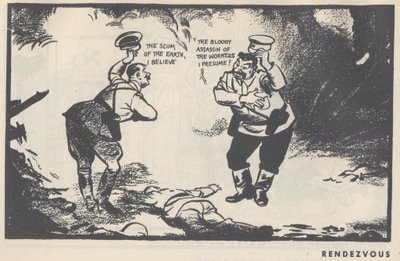

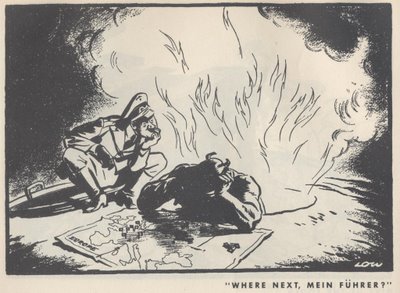

Low's art was not as simple as it looked. He later wrote, "making a cartoon occupied usually about three days: two spent in labour and one in removing the appearance of labour." You can see Low's hard work below the surface in the beautiful body language and facial expreessions of Stalin and Mussolini singing above, or in the salutations of Hitler and Stalin below. Note the tilt of the heads and the angles of the bodies. These are wonderfully choreographed drawings with simple, powerful darks and whites.

By studying the originals up close (see next image) you can see just how blunt and uncluttered Low's brushwork was. He worked large-- a typical cartoon would be 14 x 17.

I love Low's no-frills drawing. Its honesty and toughness stood up to many a powerful enemy. Low was an ardent socialist but he was so good that the staunchly conservative Lord Beaverbrook begged Low to come work for Beaverbrook's newspaper, The Evening Standard. Beaverbrook promised to double Low's salary and give him complete artistic freedom. Beaverbook later grumbled that Low was trying to comandeer the whole paper's editorial policy, but he never dared to censor Low's voice.

Hitler was enraged by Low's scathing drawings, and the Nazi government formally requested that the British government "bring influence to bear" to stop Low. However, nothing was done. After World War II, objections came from the opposite side of the fence: Winston Churchill claimed that a cartoon about the situation in Greece should be blocked "in the interests of western democracy."

Once upon a time, the ability to draw with strong, clear lines and a sharp eye could take you from a small town in New Zealand to the center of the world stage in London where powerful publishers and world leaders would rail against you, to no avail. Low was ultimately protected by the beauty and directness of his work.